In this post, I'll look at the non-combat options offered to players.

Without the Dungeon Master's Guide, this does feel like a vain effort, but it might be a worthy thought experiment. I hope it is!

In another time and place, I'd take the time to comb through the Player's Handbook to examine every single class- or race-specific option. For now, I'm just going to use the experiences of my players in the Lost Mine of Phandelver Starter Set.

The big categories of non-combat experiences in Dungeons and Dragons take the form of NPC encounters (as opposed to "monster encounters"), exploration/interaction, and downtime.

NPC encounters are those kinds of event which usually involve roleplaying: diplomacy, bluffing/deceit, persuasion, and occasionally awkward or unusual communication. Exploration and interaction are (in brief) all the things a Bard might do in a dungeon besides fight: skill checks of many kinds, for a variety of reasons; among them would be looking for traps/loot/enemies, tracking down clues and putting them together to form conclusions, moving around a space in any way other than walking across a dry flat surface, pickpocketing, sneaking, recalling knowledge, bandaging wounds, controlling animals, perceiving something hidden (in another person), surviving in a difficult environment, or (of course) participating in a performance. Downtime activities are nothing new to D&D, but they are somewhat new to the players' side of the screen. They include all of the activities a character might participate in "off-stage" or between the stages of a campaign. (Use your imagination: hobbies, research, relationships, construction, travel, etc.!)

NPC encounters and exploration/interaction are both handled (in rules-terms) through the skills mechanic. I could probably do an entire post just on how the skills have evolved over time, but I'm going to look at them through my own lens and (where appropriate) relate them back to 3e--the skill beast.

1) NPC encounters have been reduced to Deceive or Persuade. You want to convince that ogre that you're really a dragon in disguise? Be my guest: deceive him. You want to convince him that he should part with his sack of loot in exchange for what you believe is a fair (if low) price? Be my guest: persuade him. In 3e, the skills of Bluff and Diplomacy often served the same functions, but I like the elegance of the 5e system. Where Bluff was generally for short, simple deceptions, you also had Disguise for more elaborate ones, and Diplomacy itself could be used to lie in certain situations. Basically, Diplomacy was a morally ambiguous skill: both thieves and judges would need to take a few ranks in it to be savvy in their respective dealings with the law. In 5e, this is much clearer: acting in good faith? Use Persuade. Purposefully deceiving someone? Deceive is for you. Simple, clean, and uncluttered by a multitude of "sub-skills." (As a side note, Insight and Intimidation function much the same as they have in previous editions.)

2) Exploration and interaction skills compose the entire rest of the set. In general, 5e follows the same idea of "skill condensing" that 4e did. A few key notes:

Athletics and Acrobatics form a binary relationship. Does your task require strength, power, or strength-conditioning? It's an Athletics check: swimming, climbing, breaking, etc. Does your task require dexterity, agility, or balance-conditioning? It's an Acrobatics check: balancing, dodging, and maneuvering are all Acrobatics. Whatever physical ordeal your character faces, it should be a binary choice of skill.

Another interesting feature of 5e is the change from Spot, Listen, and Search to Perception and Investigation. At first blush, it looked as though Spot/Listen formed a perfect analogue with Perception, while Investigation would be the counterpart to Search. This is not the case. Perception is used for Spot(ting) and Listen(ing), but it is also used for Search(ing). Investigation is an entirely new idea: the designers wanted a metric for problem-solving (with clues), for putting clues together to form a conclusion, or to recognize the clues that are in plain sight. I like this dynamic because it creates a situation where a character who is tremendously good at seeing the strange symbols on the walls will not always be the same character who makes sense of them.

3) Finally, the "new guy" in the Player's Handbook: Downtime. In a section titled "Between Adventures" there are several suggestions for how a character might spend his/her downtime. Some options are fluffy rather than stat-oriented, but all of them have a real effect: your character has a place to go when he/she is not adventuring, and is able to continue to develop as a sentient being while not crawling around in dungeons: crafting, working, healing, researching, and learning are all presented as reasonable and valuable options.

I must admit, I cannot remember the last time that I have given characters "downtime." Usually, characters were rushed from one last-minute-save-the-world-scenario to another, with the one notable exception of going to large cities to shop for new toys. I rather look forward to giving characters downtime in the future, although I don't know if these rules were in place when the current campaign path was being drafted; it seems unlikely given the subject matter that there will be an ample amount of downtime in Tyranny of Dragons. One thing downtime would allow is a place for characters to invest their hard-won gold since they won't be buying up magic items with it.

Final verdict on the new take on skills is that it seems to combine the best of both worlds. Characters still have a variety of useful skills, and they routinely (but not often) get better at them via their proficiency bonuses. Skills are mostly intuitive and every character is proficient in a variety of them; bounded accuracy ensures that even the least perceptive character should still feel useful making Perception checks to search a room or look for danger. Characters have options to participate in the world right from the get go that don't always have to involve adventuring, and their options that do involve adventuring don't always have to involve combat.

It's a well-rounded system. I look forward to seeing how it plays out as characters reach higher and higher tiers of play.

Wednesday, November 26, 2014

Monday, November 24, 2014

D&D 5e: The Lost Mine of Phandelver

Slight detour from my discussion of the new edition as a whole to jot down some thoughts on the 5e Starter Set and the first real adventure for new DMs and players in this new edition: Lost Mine of Phandelver. Spoilers definitely ahead.

My players all really enjoyed the edition's new focus on having a backstory before the campaign ever begins; bonds, flaws, and traits are all a welcome cheat-sheet allowing characters to be played at a glance (instead of making it up as you go along). In Phandelver, that took the form of the characters each having an intimate tie to the area--or at least a reason to go there. On the downside, those reasons dropped off as the sessions continued. It took us nine sessions to go through all of the content in the Starter Set. By the end of the first two-to-three sessions (after Sildar has been rescued), the Paladin (a Fighter if you're using the pre-fabs) has already accomplished the goal he set out to meet. Granted, Sildar is a new authority figure, and if your martial character finds a home in the Lord's Alliance you're still in business. Similarly, by halfway through the adventure, the Rogue's nemeses are mostly destroyed: the Redbrands are dismantled one way or the other. Only the Cleric has a real (bonded) reason to persist in the adventure: each leg of the journey introduces another peril to one of his three cousins, whom he supposedly values more highly than almost anything else. The biggest problem I see is for the Wizard: after the shrine at Cragmaw Castle has been re-consecrated or un-desecrated, why is this acolyte of Oghma still around? Again, not a big deal to find some reason for this Wizard to continue adventuring with the party, but there's very little guidance for new DMs on how to solve this issue.

Factions. They're a great idea--allowing DMs to bring the party anywhere on Toril and still find some connection back to the characters' ideals and goals by having world-wide connections. Similarly, these factions offer some trustworthy benefactors who have the characters best interests in mind (or at least, if not their personal interests, then their goals and ideals). At my virtual table, this time around, we had a pretty good variety of interests and goals for the characters--but none of them particularly meshed well with "preserving the natural world." As such, by the end we ended up with a pair of Harpers, a member of the Lord's Alliance, and a member of the Order of the Gauntlet. For experienced players, this was a very new experience. When I ran games in previous editions, the party might have worked with the Harpers on occasion, but it was always in a mercenary agreement or where the entire party was trusted and hired by the Harpers. The idea that these separately motivated adventurers could be part of different "companies" is both engaging and new. For new players, this will be seamless (because without prior experience, they'll be able to assimilate this idea readily.)

Realistic villains. When approaching the "big bad" of Tresendar Manor and the "big bad" of Wave Echo Cave, the PCs blew through waves of guards then (in one case) went looking for him but couldn't find him and (in the second case) was confronted by him, only to have him turn invisible and run away. This absolutely puzzled my players in both cases. As my wife put it (paraphrased), the big bad is supposed to be a much higher level than the players--he's supposed to be fearless against these lesser heroes. Basically, villains in earlier in editions, in video games, and often on television are so filled with hubris that they don't even conceive of defeat as an option and therefore end up in big battle-to-the-death showdowns because they don't think they can lose until its too late. Both Glasstaff of the Redbrands and the Black Spider of Wave Echo Cave are smart villains. They recognized that alone (or even with a few key allies) their chance of success against four heavily armed and experienced heroes was not assured. The coward Glasstaff ran after he realized how far the interlopers had come and abandoned his little "fiefdom" to save his life. That's not to say he isn't going to hold a grudge, but rather that he valued his life above holding onto a stinky basement and a two-bit town. The Black Spider was even bolder and more clever; he knew that the Cleric valued his cousins' lives and had kidnapped one (after killing another) to ensure that he had an immutable bargaining chip. The PCs took one look at him, decided that the poor captured dwarf's life was already forfeit, and attacked. The Spider was incensed and frankly surprised--as was the remaining dwarf cousin--that the heroes so callously threw Nundro's life aside as forfeit and attacked. Against such bloodthirsty mercenaries (as the Spider will think of these adventurers from here on in) who cut their way through both his own forces and the magical forces he was slowly working to circumvent, he saw no options for success, killed the dwarf hostage (Nundro), and got out of there. Again, villains are expected to fight to the death, but they shouldn't unless they've run out of options and escape hatches, and/or are too foolish to have avoided a deadly fight in the first place. I really did enjoy the villains varied quirks and motivations. Not every villain was evil, and not every evil person was a villain. According to some limited feedback from my players, they enjoyed the "realness" of the people they encountered even if they were confused when villains didn't always want a showdown to the death.

The varied scope of the adventure (some sandboxing, some dungeon crawling, some wilderness encounters) provided a nice mix of opportunities for players to get used to the game. I think this was the correct choice for a Starter Set. Having said that, some of my players felt overwhelmed with the number of options available--not because having options was a bad thing, but because none of the options seemed like the best option. To put it another way, the goal was never in clear focus. Some of my most memorable campaigns included one or more sandbox elements; in fact, I think some of my players' favorite adventure with me was a city-sandbox I'd invented in which a wizards' faction had taken over the city and martial law had been declared. Different noble houses were each bunkered down, and the only way to travel safely from place to place in the city was to know who was in charge where, and to curry favor appropriately. The party had to slowly move through the city, deciding what order to approach the factions in, slowly gaining support for a coup to overthrow the wizards who had taken over the city. There was still tons of choice (Do we involve the sea captains in the coup? Can we trust the wizards' home faction to not betray the rest? How can we make it all the way to the Mayoral Estate without having to fight the wizards' demonic forces?) but the end goal was clear and all of the options (to some degree) were focused on this final objective: saving the city. While Phandelver's choices offer verisimilitude and were (behind-the-screen) almost entirely linked to what was going on in the Mines themselves, those connections were not visible to the characters. The language of "main quest" and "side quest" became popular very quickly. There is nothing wrong with this nomenclature except that these are 21st century players; they're used to needing a certain amount of experience/power before advancing the main quest is a good idea, and side quests often offer certain rewards that will not be offered in a main quest. My players' party did every single "side quest" available--putting off the "time-sensitive" examination of the Mine itself and delaying an investigation into the southerly town of Greenest. Why? Because the side-quests were undone and were likely to yield rewards that would help with the main quest. In reality, no tangible rewards came of those side-quests except the experience points required to level up (which, ultimately, they would have gotten in the main quest). Not that a red herring or an unrelated adventure can't break up monotony, but in this case I think it made the players feel like they were either (A) missing out on the big picture or (B) wasting their time. (What was the deal with that banshee anyway? Why is that necromancer camped out at the Old Owl Well? Who's going to deal with that dragon in Thundertree?) Some of the questions that arose are natural, some are lingering because of the focus on "main quest" in previous editions/campaigns. We'll see how this evolves from there.

Onward to Hoard of the Dragon Queen!

My players all really enjoyed the edition's new focus on having a backstory before the campaign ever begins; bonds, flaws, and traits are all a welcome cheat-sheet allowing characters to be played at a glance (instead of making it up as you go along). In Phandelver, that took the form of the characters each having an intimate tie to the area--or at least a reason to go there. On the downside, those reasons dropped off as the sessions continued. It took us nine sessions to go through all of the content in the Starter Set. By the end of the first two-to-three sessions (after Sildar has been rescued), the Paladin (a Fighter if you're using the pre-fabs) has already accomplished the goal he set out to meet. Granted, Sildar is a new authority figure, and if your martial character finds a home in the Lord's Alliance you're still in business. Similarly, by halfway through the adventure, the Rogue's nemeses are mostly destroyed: the Redbrands are dismantled one way or the other. Only the Cleric has a real (bonded) reason to persist in the adventure: each leg of the journey introduces another peril to one of his three cousins, whom he supposedly values more highly than almost anything else. The biggest problem I see is for the Wizard: after the shrine at Cragmaw Castle has been re-consecrated or un-desecrated, why is this acolyte of Oghma still around? Again, not a big deal to find some reason for this Wizard to continue adventuring with the party, but there's very little guidance for new DMs on how to solve this issue.

Factions. They're a great idea--allowing DMs to bring the party anywhere on Toril and still find some connection back to the characters' ideals and goals by having world-wide connections. Similarly, these factions offer some trustworthy benefactors who have the characters best interests in mind (or at least, if not their personal interests, then their goals and ideals). At my virtual table, this time around, we had a pretty good variety of interests and goals for the characters--but none of them particularly meshed well with "preserving the natural world." As such, by the end we ended up with a pair of Harpers, a member of the Lord's Alliance, and a member of the Order of the Gauntlet. For experienced players, this was a very new experience. When I ran games in previous editions, the party might have worked with the Harpers on occasion, but it was always in a mercenary agreement or where the entire party was trusted and hired by the Harpers. The idea that these separately motivated adventurers could be part of different "companies" is both engaging and new. For new players, this will be seamless (because without prior experience, they'll be able to assimilate this idea readily.)

Realistic villains. When approaching the "big bad" of Tresendar Manor and the "big bad" of Wave Echo Cave, the PCs blew through waves of guards then (in one case) went looking for him but couldn't find him and (in the second case) was confronted by him, only to have him turn invisible and run away. This absolutely puzzled my players in both cases. As my wife put it (paraphrased), the big bad is supposed to be a much higher level than the players--he's supposed to be fearless against these lesser heroes. Basically, villains in earlier in editions, in video games, and often on television are so filled with hubris that they don't even conceive of defeat as an option and therefore end up in big battle-to-the-death showdowns because they don't think they can lose until its too late. Both Glasstaff of the Redbrands and the Black Spider of Wave Echo Cave are smart villains. They recognized that alone (or even with a few key allies) their chance of success against four heavily armed and experienced heroes was not assured. The coward Glasstaff ran after he realized how far the interlopers had come and abandoned his little "fiefdom" to save his life. That's not to say he isn't going to hold a grudge, but rather that he valued his life above holding onto a stinky basement and a two-bit town. The Black Spider was even bolder and more clever; he knew that the Cleric valued his cousins' lives and had kidnapped one (after killing another) to ensure that he had an immutable bargaining chip. The PCs took one look at him, decided that the poor captured dwarf's life was already forfeit, and attacked. The Spider was incensed and frankly surprised--as was the remaining dwarf cousin--that the heroes so callously threw Nundro's life aside as forfeit and attacked. Against such bloodthirsty mercenaries (as the Spider will think of these adventurers from here on in) who cut their way through both his own forces and the magical forces he was slowly working to circumvent, he saw no options for success, killed the dwarf hostage (Nundro), and got out of there. Again, villains are expected to fight to the death, but they shouldn't unless they've run out of options and escape hatches, and/or are too foolish to have avoided a deadly fight in the first place. I really did enjoy the villains varied quirks and motivations. Not every villain was evil, and not every evil person was a villain. According to some limited feedback from my players, they enjoyed the "realness" of the people they encountered even if they were confused when villains didn't always want a showdown to the death.

The varied scope of the adventure (some sandboxing, some dungeon crawling, some wilderness encounters) provided a nice mix of opportunities for players to get used to the game. I think this was the correct choice for a Starter Set. Having said that, some of my players felt overwhelmed with the number of options available--not because having options was a bad thing, but because none of the options seemed like the best option. To put it another way, the goal was never in clear focus. Some of my most memorable campaigns included one or more sandbox elements; in fact, I think some of my players' favorite adventure with me was a city-sandbox I'd invented in which a wizards' faction had taken over the city and martial law had been declared. Different noble houses were each bunkered down, and the only way to travel safely from place to place in the city was to know who was in charge where, and to curry favor appropriately. The party had to slowly move through the city, deciding what order to approach the factions in, slowly gaining support for a coup to overthrow the wizards who had taken over the city. There was still tons of choice (Do we involve the sea captains in the coup? Can we trust the wizards' home faction to not betray the rest? How can we make it all the way to the Mayoral Estate without having to fight the wizards' demonic forces?) but the end goal was clear and all of the options (to some degree) were focused on this final objective: saving the city. While Phandelver's choices offer verisimilitude and were (behind-the-screen) almost entirely linked to what was going on in the Mines themselves, those connections were not visible to the characters. The language of "main quest" and "side quest" became popular very quickly. There is nothing wrong with this nomenclature except that these are 21st century players; they're used to needing a certain amount of experience/power before advancing the main quest is a good idea, and side quests often offer certain rewards that will not be offered in a main quest. My players' party did every single "side quest" available--putting off the "time-sensitive" examination of the Mine itself and delaying an investigation into the southerly town of Greenest. Why? Because the side-quests were undone and were likely to yield rewards that would help with the main quest. In reality, no tangible rewards came of those side-quests except the experience points required to level up (which, ultimately, they would have gotten in the main quest). Not that a red herring or an unrelated adventure can't break up monotony, but in this case I think it made the players feel like they were either (A) missing out on the big picture or (B) wasting their time. (What was the deal with that banshee anyway? Why is that necromancer camped out at the Old Owl Well? Who's going to deal with that dragon in Thundertree?) Some of the questions that arose are natural, some are lingering because of the focus on "main quest" in previous editions/campaigns. We'll see how this evolves from there.

Onward to Hoard of the Dragon Queen!

Sunday, November 23, 2014

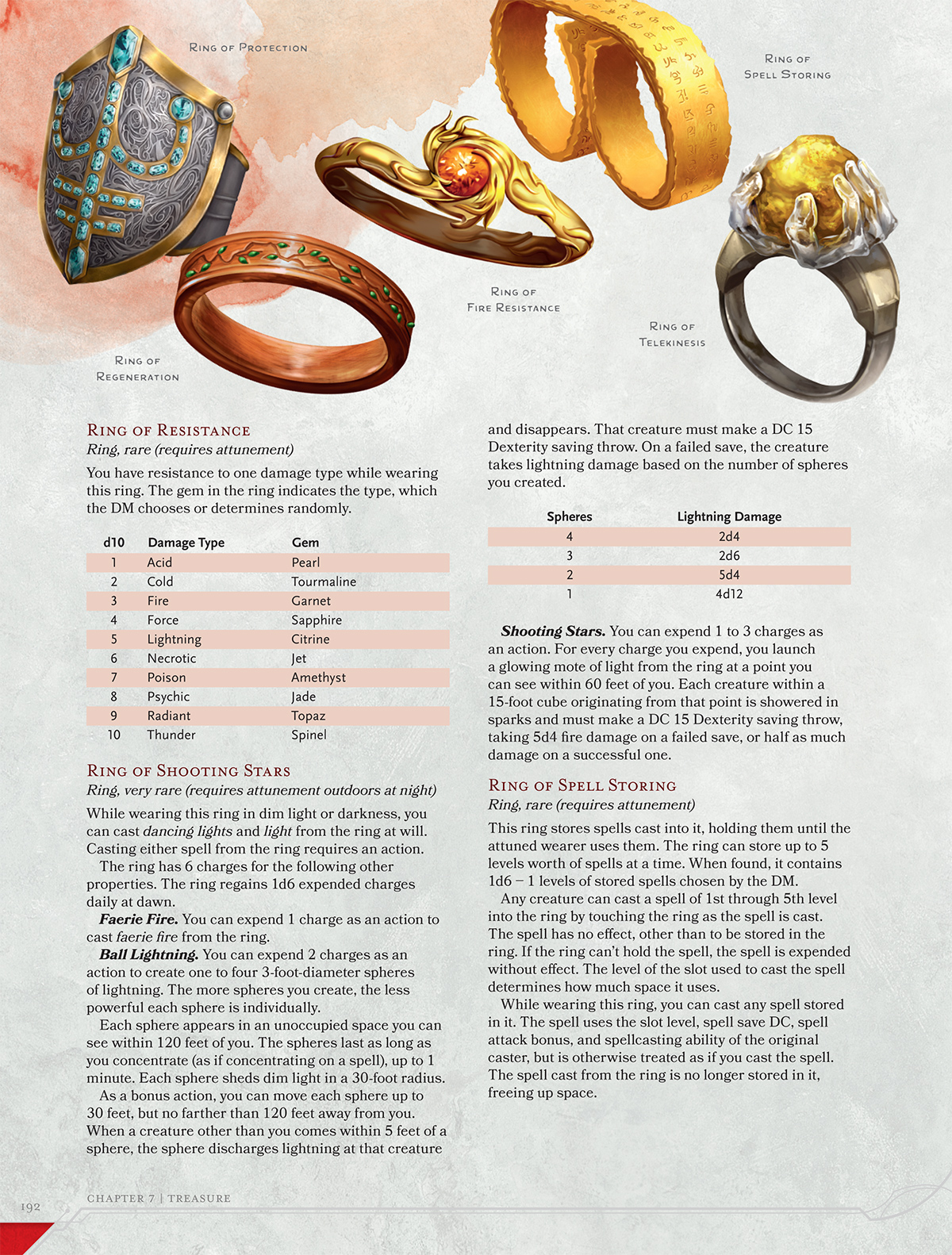

D&D 5e: Magic Items

Magic items are a strange beast in 5e. Because of the whole bounded accuracy dynamic, there isn't a need for magical arms, armor, or gizmos in order to be appropriately powerful at a given level. I am already seeing how this change is playing out in the treasure being portioned: it lowers the amount of magical treasure significantly. In 3e, martial characters looked for that +1 longsword as soon as they started a campaign. Once they had it, it was time to look for a +2 longsword, and so on. Finding each tier of magical item (all the way up to the +5 bonus) was partly a form of "keeping up with the Baggins" and partly a way to measure the success of the party/character. The better armed and armored your character was, the more successful you were as a player. This dynamic is fundamentally shifted once magic items become useful, somewhat privileged, and not required.

As with many other changes from previous editions, this should not hit new players particularly hard. In fact, the idea that a magic item is now something precious and special should make each individual magic-item-find that much more exciting. I think it will feel much more like Lord of the Rings and less like it used to in 3e.

A low-magic Forgotten Realms universe is a strange thing to contemplate for me, but not a completely awkward one. I am going to be very interested indeed to see how Keith Baker's Eberron setting comes to pass in 5e. (His comments on his own webpage suggest that in the high-magic third edition, Warforged were overpowered. His thoughts on their redesign bring that power-creep down significantly.)

The place where the magic item dearth shows up most prominently is in the published adventure paths beyond Lost Mine of Phandelver: the Tyranny of Dragons adventure path(s). The designers, working with unfinished treasure rules, placed almost no magic items into the adventures. And really, until the Dungeon Master's Guide is released, we peons who are making do with the Player's Handbook and Monster Manual are going to find it hard to compensate appropriately. For right now, I'm planning to run the adventures without adjusting the treasure amounts, though I know it will seem somewhat low.

Maybe the biggest change in magic items (from 3e-4e) is in the fact that they're (at the time I'm writing this) no longer associated with a gold value. This one really didn't sink in until I started re-reading the magic item descriptions in the published adventures: gems and art objects are given "sell" values in gold, but magic items are just...magic items (with a few notable exceptions). Apparently, since magic (or physical manifestations of magic) is/are far less common than they were in previous editions, there are no "magic item stores." Some are even postulating that heroes will have little to spend their hard-earned gold on since they won't be able to go into larger cities and buy new magical equipment with it.

I must admit that the lack of pricing certainly sends up red flags for me. If there is no economy for magical items, that makes each one an anomaly or a priceless artifact--and I don't think that's strictly true. Potions of healing are, for better or worse, a staple of the economy and have a set price value in the Player's Handbook relative to other non-magical gear. Why shouldn't other magical items have the same treatment? The values could certainly be exaggerated for the commissioning or purchasing of such items--and the return for selling them on the open market could be lowered to reflect the uncertainty of finding a buyer--but to ignore that altogether would be a mistake.

Heroes will always find something to spend their cash on (fortresses? servants? charity? non-magical assistance?), but magic items--and the economy thereof--have been such an important part of the game for so many years that I will be hard pressed to move my players (and me!) to the new normal.

As with many other changes from previous editions, this should not hit new players particularly hard. In fact, the idea that a magic item is now something precious and special should make each individual magic-item-find that much more exciting. I think it will feel much more like Lord of the Rings and less like it used to in 3e.

A low-magic Forgotten Realms universe is a strange thing to contemplate for me, but not a completely awkward one. I am going to be very interested indeed to see how Keith Baker's Eberron setting comes to pass in 5e. (His comments on his own webpage suggest that in the high-magic third edition, Warforged were overpowered. His thoughts on their redesign bring that power-creep down significantly.)

The place where the magic item dearth shows up most prominently is in the published adventure paths beyond Lost Mine of Phandelver: the Tyranny of Dragons adventure path(s). The designers, working with unfinished treasure rules, placed almost no magic items into the adventures. And really, until the Dungeon Master's Guide is released, we peons who are making do with the Player's Handbook and Monster Manual are going to find it hard to compensate appropriately. For right now, I'm planning to run the adventures without adjusting the treasure amounts, though I know it will seem somewhat low.

Maybe the biggest change in magic items (from 3e-4e) is in the fact that they're (at the time I'm writing this) no longer associated with a gold value. This one really didn't sink in until I started re-reading the magic item descriptions in the published adventures: gems and art objects are given "sell" values in gold, but magic items are just...magic items (with a few notable exceptions). Apparently, since magic (or physical manifestations of magic) is/are far less common than they were in previous editions, there are no "magic item stores." Some are even postulating that heroes will have little to spend their hard-earned gold on since they won't be able to go into larger cities and buy new magical equipment with it.

I must admit that the lack of pricing certainly sends up red flags for me. If there is no economy for magical items, that makes each one an anomaly or a priceless artifact--and I don't think that's strictly true. Potions of healing are, for better or worse, a staple of the economy and have a set price value in the Player's Handbook relative to other non-magical gear. Why shouldn't other magical items have the same treatment? The values could certainly be exaggerated for the commissioning or purchasing of such items--and the return for selling them on the open market could be lowered to reflect the uncertainty of finding a buyer--but to ignore that altogether would be a mistake.

Heroes will always find something to spend their cash on (fortresses? servants? charity? non-magical assistance?), but magic items--and the economy thereof--have been such an important part of the game for so many years that I will be hard pressed to move my players (and me!) to the new normal.

Saturday, November 1, 2014

D&D 5e: Players Rule (or: Players' Rules), Part 2

In my last post, I started by articulating my thoughts on experience gain and leveling up. Before I continue the discussion on how the rules affect players, I thought I'd formally address something that came up in the discussion about my post in the comments:

The dual leveling systems in 5e (loosely called "experience gain" and "milestone") work in tandem. Below are my thoughts on this from the comments:

"The experience points tell players how significant their characters' encounter was or how epic their solution was. It also allows players (particularly at higher levels) to feel like they're 'getting somewhere' and to have a gauge as to how soon they'll get to use that fancy new ability they get when their character levels up!

That's why I like the current edition's focus on both styles: it's good for the players. If they just fight a whole bunch of random monsters because they're exploring, they may level before they ordinarily would based on the campaign/story being told. If they think of clever, interesting ways to circumvent some of the [expected/story] encounters and get to the next part of the story, they're rewarded with a level rather than punished by being required to grind."

Combat:

In 3e, combat was an arithmetical nightmare. The DMG advised DMs to make use of a simple rule: if a condition is advantageous, grant a +2 bonus. If a condition is disadvantageous, grant a -2 penalty. Bard songs, cleric spells, armor bonuses, feat bonuses, ability bonuses, and conditional modifiers all played a role in what the end modifier would be. Most of these modifiers changed on a round-to-round basis. Worst of all, these bonuses sometimes mattered an awful lot (when an encounter was perfectly matched) and sometimes mattered not at all (ever see a band of mid-level adventurers tearing through a bunch of low-level monsters?). I loved 3e and 3.5e, don't get me wrong, but that list of stats was obnoxious to keep track of--both for players and Dungeon Masters.

In 4e, combat became a video game with hot-keys. Most of the stats were static, and the ones that were dynamic were usually linked to a named condition--something that could be flagged or indicated in a visual way (presumably to help players remember that the lich was flying, the zombies were slowed, and their Paladin was blessed). The modifiers were less omnipresent, but the combat itself as a bit more flat (for a different reason). When every player essentially "cast a spell" every turn, and most of those "spells" or abilities were just stand-ins for what used to be called a "basic attack," it slowed combat down. In retrospect, I think I know why: no matter how often we played, when presented with a bunch of similar options, players were constantly trying to decide which option would be best among the similar choices. The only place I see this come up in 5e is with wizards and cantrips. (Do I cast ray of frost or fire bolt?)

In 5e, combat most closely resembles 3e. It no longer feels like players and monsters are hitting their hot-keys. It also doesn't feel like I need a white-board for each player tracking constantly shifting modifiers. Where once the DM was asked to consider +2 or -2 (which, let's be honest, quickly became a moot modifier because of "unbounded accuracy"), now players can seek out conditions that negate disadvantage or which grant advantage. We have returned to an era of "basic attacks," but the mechanics are much more forgiving on non-spellcasting classes as far as giving them options in combat.

I'd like to start by considering the spellcasters (Clerics and Wizards) and move to the more martial classes. Unfortunately, since my party has a Paladin instead of a Fighter, I can't necessarily say how "the big four" have changed, though you can certainly extrapolate.

Wizards function almost identically to their 3e counterparts with a couple of very interesting "borrows" from 4e:

- Cantrips: being able to cast basic--but useful and scaling--spells at-will is a wonderful boost to all spellcasters being magical all the time (not just while they have spell slots available).

- Short Rest Restoration: Arcane Recovery is a fascinating way to counter the "whelp, Wizard's out of spells, time to camp for the night" issue. This criticism is a common--and accurate--issue with the way D&D has worked in the past. 4e made everyone a spellcaster (in a sense) to overcome the problem. I think I like this solution somewhat better; Wizards get fewer spell slots than their 3e counterparts, but can get some of them back.

- Concentration: In 3e (and to a certain extent in 4e), concentration was a reactionary effect that came into play when players took damage or when they were trying to "cast defensively." By removing the defensive casting mechanic, and only allowing Wizards (or any caster) to maintain concentration on one spell at a time, it not only limited some of the spellcasting abuses (I'm looking at you party-buff mules), but it also eliminated a step from Wizards casting spells in combat, streamlining every round of combat.

- Not all Clerics get heavy armor.

- Domains matter for gameplay styling right from the get go.

- Removing the "minor" or "swift" actions, Clerics having spells that can only be cast as a reaction changes how/when they heal.

- The concentration rules (see above) affect Cleric spellcasting too.

- Removing the rules for "flanking" has ironically made it 10x easier for Rogues to activate their Sneak Attack ability. Basically, if the party tank is in combat, the Rogue can drop whoever the tank is fighting--even at a distance.

- Bonus Actions have added a whole new lair of dastardly to Rogues. By letting rogues (essentially) move, Sneak Attack, and ignore opportunity attacks while remain out of range of the majority of bad guys, Rogues can maintain a very high damage output while staying safe in combat.

- What makes the above two so wicked is that characters can now move, act, and then finish their movement--something that was not available before.

- Heavy armor, shields, and spells, and Lay on Hands make Paladins just as durable as they used to be.

- Opening up Divine Sense (formerly Detect Evil) and Divine Smite (formerly Smite Evil) makes Paladins a little bit less of a one-trick pony. Fighting beasts in the forest instead of a cadre of demons? No problem!

- Fighting Style lets Paladins (like Fighters) specialize a bit into a particular role. In our campaign, the Paladin is a tank who wants to deal damage, but knows he has to take it before he can dish it out; he took the flat +1 bonus to AC (and rightfully so, I think).

- Hit points have been more boosted at the low end (d6 for Wizards!) making everyone a tiny bit less fragile by default.

- Monsters--even at low levels--have surprisingly high numbers of hit points. There are no more "minions" as there were in 4e. If you're fighting a horde, be prepared to slog through it; a fireball won't insta-kill them all anymore (though a sufficiently powerful one might).

- Ignoring the "diagonal movement on a grid is different" reality (as was done in 4e) remains in 5e. 95% of the time, it doesn't matter that much. The 5% of the times it does matter, it usually benefits the players, so I'm okay with it.

- So far, advantage works. It works really well. (So does disadvantage.)

- Bounded accuracy is already showing up in combat at low levels--for the better. The Paladin (used to being the only one in previous editions that could hit monsters routinely) is becoming frustrated that he isn't auto-hitting. The Rogue is dishing out damage on fleshy/robust but unarmored enemies. The Wizard can land ray of frost without worrying about a saving throw from the enemy. The Cleric knows exactly how much that buff spell is going to be worth because he can look at one set of numbers (remember, all those ugly modifiers from 3e are gone). Every monster is a potential threat, but tactics still help defeat monsters more quickly and more safely.

Next time, I'll look at non-combat options.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)