Here are our five new bits of wisdom:

Adventure Time...

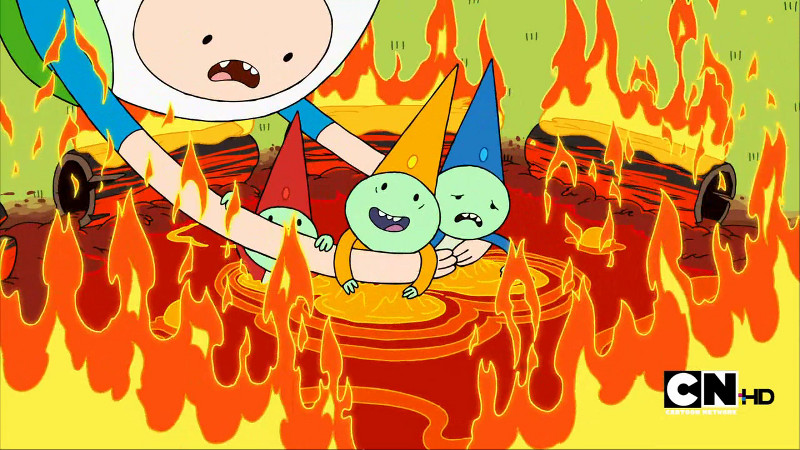

- Lets us view the setting (the Land of Ooo) through the eyes of a human, but consistently shows us sentient races which are both inhuman (crazy candy people! sentient fire!) and humane (compassionate, feeling, loving, friendship-seeking creatures).

- Is brief and episodic, but often ties episodes together into a longer story or campaign.

- Admits real consequences for the actions of the adventurers, but never lets those actions end the story.

- Has characters grow in experience and power; they possess unusual or even unique abilities.

- Accepts that characters have a home base from which most of their adventuring is launched.

1. Lets us view the setting through the eyes of a human, but consistently shows us sentient races which are both inhuman and humane.

As DMs, it's important to balance the magical and the mundane. It's also important to balance the human and the humane from the totally alien and inhumane. A campaign where every nonhuman is completely inscrutable ends up looking like an Alien vs. Predator remix at best, and an ant farm at worst. Non-humans and particularly the wildly different non-humans (non-playable races who are sentient) need to be a mixed bag.

An insane, inscrutable, unfathomable Kuo-Toa fishing group might save the adventurers from a drow war band and provide them with food and shelter. A myconid colony might see the adventurers as a mono-minded disease which has to be eradicated to protect the sprouts of the colony. A lone Thri-keen explorer may fall in with the party for safety, but become so frustrated by their lack of order and organization that it leaves them for a route which promises certain death.

What do all of these examples have in common? They each offer opportunities for the party to be

human (and humane) to creatures who are not.

Some of the coolest interactions in Adventure Time happen as Finn (or, to a lesser extent, Jake) tries to be a hero--compassionate and humane--and finds that his own paradigm might be flawed for the species or culture which he is trying to help. Ultimately, Finn either has to gamble that his morality is universal (often) or that his choices were made based on culture rather than morality, and therefore he needs to adjust (sometimes). These are the interesting situations players should find their players in!

Some of the coolest interactions in Adventure Time happen as Finn (or, to a lesser extent, Jake) tries to be a hero--compassionate and humane--and finds that his own paradigm might be flawed for the species or culture which he is trying to help. Ultimately, Finn either has to gamble that his morality is universal (often) or that his choices were made based on culture rather than morality, and therefore he needs to adjust (sometimes). These are the interesting situations players should find their players in!Characters need to be put in situations where their own way of doing things is not universally accepted--and occasionally, in which their own version of the "right" thing might be questionable.

2. Is brief and episodic, but often ties episodes together into a longer story or campaign.

In 11 minutes, Adventure Time tells elaborate, thoughtful, and complete stories. They introduce characters, provide setbacks, reach an emotional climax, and resolve. Sometimes, they take a whole 22 minutes to tell these stories, and without the audience ever really noticing they unveil a plot over the course of many separate, disparate stories. Think of any of your favorite story-lines from Adventure Time (the redemption of the Ice King, Finn's love life, the history of the Candy Kingdom) and you see that while the plot you're thinking of comes into focus for an episode or two, it just as quickly fades into the background, not to be seen or thought of for several more episodes (or seasons!).

So how do we replicate this complicated weaving of adventures into campaigns, where every adventure doesn't have to focus on the same thing?

Freud is attributed with the saying that "sometimes a cigar is just a cigar." In other words, sometimes a dungeon is just a dungeon, that wandering monster is just another way of earning experience, and the weird peddler with the third eye is just a curiosity. On the other hand...

To a certain extent, Finn and Jake's adventures are consistently flirting with 21st century irony: we're never supposed to know if the ominous skeletal beggar is really evil, or if he's just a natural feature of his environment. (On the other hand, flim-flammers like the King of Ooo are almost always to be distrusted.) The bottom line is that the world is endlessly complicated, and sometimes our heroes simply cannot follow the thread of a "campaign" continuously. They hit dead ends, they get distracted by other forces or problems, and they run out of ideas.

To a certain extent, Finn and Jake's adventures are consistently flirting with 21st century irony: we're never supposed to know if the ominous skeletal beggar is really evil, or if he's just a natural feature of his environment. (On the other hand, flim-flammers like the King of Ooo are almost always to be distrusted.) The bottom line is that the world is endlessly complicated, and sometimes our heroes simply cannot follow the thread of a "campaign" continuously. They hit dead ends, they get distracted by other forces or problems, and they run out of ideas.Try to keep "adventures" brief, ideally wrapping them up after a session or two. Similarly, it's okay to have interludes in campaigns. Many loose threads can be fun--as long as the players don't feel like all of them have to be undertaken (or even can be undertaken) immediately or simultaneously.

3. Admits real consequences for the actions of the adventurers, but never lets those actions end the story.

Many forms of entertainment follow the advice of Philip J. Fry: "It [is] just a matter of knowing the secret of all TV shows: at the end of the episode, everything's always right back to normal."

Adventure Time doesn't allow this to be the case; DMs cannot allow this to be the case either. The exploits of Finn and Jake are not temporary and entertaining interchangeable jaunts, they are moments of development both for the characters and the world they inhabit. This isn't to say that some adventures cannot have a goal of getting things "back to how they were," but it should never be a complete success.

For example, one of the earliest episodes introduces Marceline the Vampire Queen as the original (or at least prior) owner of Finn and Jake's tree-house. The entire episode is spent trying to get comfortable outside the tree-house or to take it back from Marceline. While they do eventually get their tree-house back, everything has changed: Marceline is now (for better or worse!) a part of their lives; their carefree sense that their world has always been "the way it is now" has been shattered; and they have been beaten (physically, anyway) by a force stronger than themselves--but spared. Not bad for 11 minutes of animation!

As DMs, it's our job to make sure that even when we introduce something that seems overwhelming (like Marceline) the way the PCs interact with this new force has real and lasting consequences--even if they are able to solve whatever initial problem the force has created in their adventure. This not only provides fuel for future adventures, but it reminds PCs that their actions have both merit and impact.

PCs' actions need to have consequences in the campaign world--even when their actions are reactions, or when the consequences are unintended or even unforeseen.

4. Has characters grow in experience and power; they possess unusual or even unique abilities.

This one may seem like a no-brainer, but it bears repeating: In the fifth edition of D&D, player characters are extraordinary individuals. Average people do not have "levels" of anything--let alone levels of an adventuring class!

When Finn and Jake are helping out average people (whether those people are humans or not!) they are consistently revealing how different they are from those people. Finn grows in wisdom, swordsmanship, and (as time goes on) deepness of voice. Jake is a unique, stretchy dog to begin with, but also grows as Finn does. They each learn from their parents, from their friends, from encounters with enemies, and from their experiences. Finn's various blades and Jake's use (or lack of use) of various weapons and implements change over time.

PCs need more than just new stuff; new items, new powers, and new heights of abilities need to be revealed and noticed by others in the campaign world. Give PCs a chance to try out the abilities and powers they're most excited about, but also try to give them opportunities to show off things they can do, but may not have thought about before.

5. Accepts that characters have a home base from which most of their adventuring is launched.

The tree-house is a textbook base of operations: it's cool looking, centrally located, easily defensible but not impregnable, has room for all of their gathered loot and armaments, and serves as a cozy home for Finn and Jake when they're not out adventuring. Perhaps best of all, they took it over rather than built it themselves, so they don't know everything about it. Sometimes they leave the tree-house to seek out adventure, other times adventure seeks them out at the tree-house.

Any time adventurers can take an abandoned fort, temple, or ruin and turn it into a new base of operations, the same effects can be had. There's nothing wrong with building something new, but try to encourage the players to build it atop an ancient ruin or near an older construction. This more easily allows adventure to find them.

Any time adventurers can take an abandoned fort, temple, or ruin and turn it into a new base of operations, the same effects can be had. There's nothing wrong with building something new, but try to encourage the players to build it atop an ancient ruin or near an older construction. This more easily allows adventure to find them.Having adventures start at a base of operations allows PCs to also have a place to store their

thousands of unmanageable copper coins, to keep their extra blades and arrows, and even gives them an excuse to interact with NPCs. (After all, BMO and NEPTR often watch over the place while Finn and Jake are away!) Having a home base gives PCs a location to work on their downtime activities (running a business, forging a sword, scribing a scroll, researching a distant location, etc.).

Whenever possible, provide a home base for PCs which is wholly their own but not entirely of their own making; allow it to be both a place which is thought of fondly and about which not everything is known. PCs should expect to both seek out adventures from their safe haven and have adventures come to them!

I hope you've enjoyed considering how your campaigns and D&D experiences might take their cues from Adventure Time! I know I have a long way to go to make all of these ideas realities in my own games, but I truly believe players will enjoy the game more thanks to these ideas. Let me know in the comments what you think about these ideas--maybe I missed a key crossover that should be covered in a future post, or there should be a revision of one of my existing ideas? As always, thanks for reading, and happy gaming!

I hope you've enjoyed considering how your campaigns and D&D experiences might take their cues from Adventure Time! I know I have a long way to go to make all of these ideas realities in my own games, but I truly believe players will enjoy the game more thanks to these ideas. Let me know in the comments what you think about these ideas--maybe I missed a key crossover that should be covered in a future post, or there should be a revision of one of my existing ideas? As always, thanks for reading, and happy gaming!

Thanks for the info.

ReplyDelete